The Weaving Widows of War

The Weaving Widows of War

In a small church in a suburb of the Philippine capital Manila, a group of women who lost their loved ones to the government's bloody war on drugs, overcome their grief by sewing and weaving.

They are of various ages and from different walks of life, but they are bound by a story of grief. They are women who are left to pick up the pieces, to struggle to survive.

They are widows who continue to work on healing the wounds that were inflicted on their lives.

In 2016, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte launched a controversial “war” — supposedly targeting criminal and drug traffickers. On the front line of his campaign are members of the national police who have gone after suspected drug users and peddlers that has resulted in what seems to be a killing spree.

The impact of the crackdown has claimed thousands of lives, mostly men — husbands, fathers and brothers. The killings have left thousands of children orphaned and women widowed.

Aileen Naty’s husband, Rannie Dagami, was killed during a police raid on a local junk shop. Police said Dagami fought back during an attempted arrest. "I still can't accept his loss," said his wife. "If he was jailed, he could've changed. No matter how bad a person is, they can still change," she added.

In the same police raid, Constantino de Juan was also killed. His wife, Lourdes, wasn’t there. She was in prison because police had earlier arrested her when they couldn’t find her husband who was on a "drugs watch list." Lourdes was still in jail, pregnant with their seventh child, when her husband was shot dead. Like most police operations, authorities reported that Constantino fought back.

In just one night, Aileen and Lourdes’s lives changed. All they wanted was to put food on the table for their children, but the drug war came knocking on their doors. Overnight, they became the new heads of their respective households.

Most of those killed in Duterte’s brutal crackdown are the poor. Independent monitoring agencies have already pegged the number of drug war-related deaths at more than 20,000.

Rodalyn Adan, 31, found herself in a similar situation as other drug-war widows. Her husband, Crisanto Abliter, was killed in an anti-drug operation in the slums of Manila’s Quezon City in 2016.

Adan said she waited for news of her husband the entire day. The next morning, a relative called her asking where the funeral was going to be. She didn't answer, and just cried. In that “drug bust,”100 people were caught while two were killed — one of whom was Adan's husband.

She has seven children. Rodalyn is now struggling to make ends meet for her family. Often she finds herself looking at photos of her family — all alive and complete — on her mobile phone.

"I'm still slowly accepting [the death]," she said. "As my children grow, so does my frustration that he won't be there with them," said Rodalyn. In the aftermath of their loss however, Rodalyn, Lourdes, and Aileen have found each other through a campaign that was "heaven-sent."

The Solidarity With Orphans and Widows, a church-backed program, began at the height of the drug war in 2016. It was a collaborative effort of several priests. Vincentian priest Danny Pilario, a Theology professor, said the project was a result of church people's first-hand encounter with Duterte’s "war on drugs."

In the slums, people would come to the church to ask priests for a blessing for their dead. They also ask for financial assistance for funeral expenses.

And people talked about their lives and faith, too. "They have a lot of problems like trauma, anger and fear. One of those problems is putting food on the table," said Father Pilario.

Then came the weaving.

In December 2018, the women were offered weaving as a livelihood program. They were taught to sew backpacks, pencil cases, and shirts.

Father Pilario said the work offered the widows dignity, which, he said, had been lost since their husbands died.

Dignity, "because now they take pride in themselves" that they can actually support their family even after what happened, he said.

It started small, but the business grew as the women learned more about the craft. The women would come in five days a week and would earn about five dollars a day. "To be able to vindicate the death of their loved ones is only possible in another time. This time, they need to live. To live means to sustain themselves," said the priest.

Their difficulties are still far from over, but at least the widows are starting to find their bearings in the aftermath of their tragic loss. "The program helps us financially. It's a good way to cope. If we stay at home, we might just end up crying. I still tear up when I see his pictures on my cellphone," said Adan.

While the income has certainly helped, the act of weaving itself with other women who share the same trauma has proved to be therapeutic. "They found community. They found a family," said Father Pilario.

It’s a tough job to raise a family as a single parent, but for the widows of Duterte's "war on drugs," threads put together can weave hope.

-

Policemen check the gun recovered from one of two unidentified drug suspects after they were shot by dead by police during a buy-bust operation in Tondo, Manila on Friday. June 8, 2018. According to an international index, the Philippines is the second least peaceful country in the Asia-Pacific due to the governmentâs relentless anti-narcotics drive and the Marawi siege.

-

Rodalyn and her children inside their home in Payatas village.

-

A man walks pas a police signage against illegal drugs in Lupang Pangako village in Quezon City.

-

Rodalyn Adan still becomes emotional when she looks at her phone with pictures of her husband, Cristanto Abliter and children.

-

Rodalyn Adan sewing.

-

Lourdes De juan sews used materials at a clothing shop in Lupang Pangako village in Quezon City.

-

Sewing materials are seen in a clothing shop as part of a livelihood program in Payatas, Quezon City where there is a group of women - all of them widows, mothers, sisters and people left behind by the drug war's slain victims.

-

-

A boy walks past a sign saying 'Land of Promise' in Payatas village, Quezon City.

-

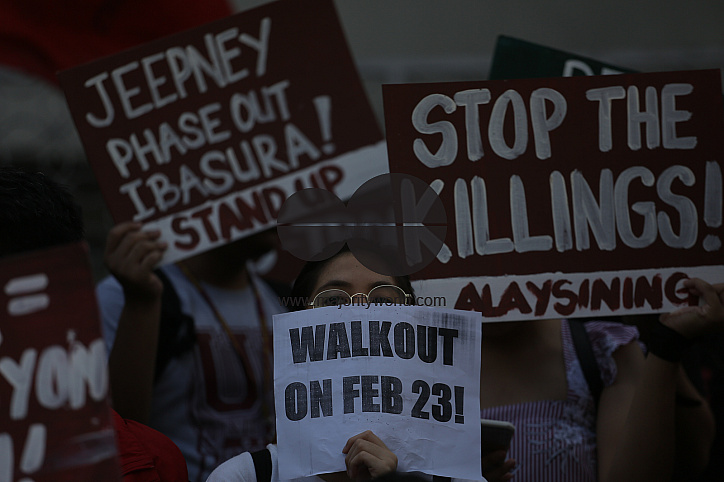

Students from the University of the Philippines walk out of their classes to protest on various issues against the Duterte administration at Palma Hall building in Quezon City on Friday. The students joined simultaneous protests in campuses against various issues in politics, the economy and human rights.

-

Aileen and her children.

-

A woman measures used materials at a Catholic church livelihood program in Payatas village in Quezon City.

-

Inside Aileen's small house in Payatas village, Quezon City.

-

-

"I still can't accept his loss. If he was jailed, he could've changed. No matter how bad a person is, they can still change." said Aileen Naty, 29. Aileen's husband, Rannie Dagami, was killed during a police anti-drug operation at a local junk shop. Police said Dagami fought back during the attempted arrest.

-

The Lupang Pangako church in Payatas, Quezon City.